inter·punct

Editor | January 2014 - June 2017

inter·punct is a journal and discussion group for architecture (and more!) founded by students at Carnegie Mellon University in 2011. The journal has released two issues, para·meter (2013) and inter·view (2016). I served as an editor of inter·view - along with Christopher Ball and Phillip Denny - and conducted and transcribed many of the interviews contained in the issue. I was also a member of the inter·punct discussion group.

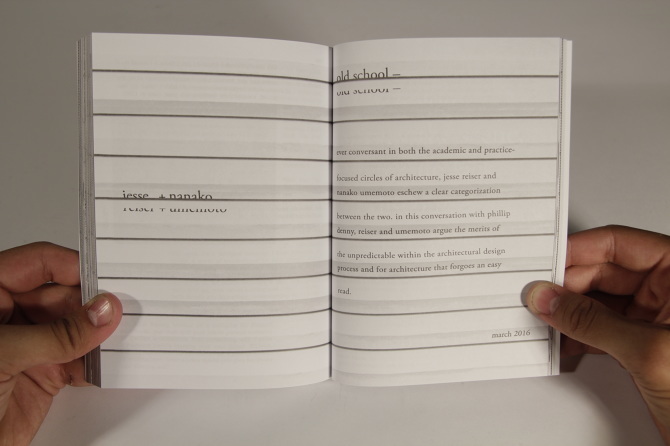

inter·view features fifteen interviews with a diverse group of noted architects and practitioners, including Maria Aiolova, Alex Maymind, Hugh Broughton, Winy Maas, Harry Gugger, Sou Fujimoto, Bernard Tschumi, Wiel Arets, José Oubrerie, Mark Pasnik, Neil Denari, Eva Franch i Gilabert, Jesse Reiser and Nanako Umemoto, Christina Ciardullo, and Vishaan Chakrabarti.

Editorial Note

We’re running late. Really late. So sorry. We wanted to get this to you sooner. Really, we did. And so, this is the long-awaited follow-up to our inaugural issue para·meter.

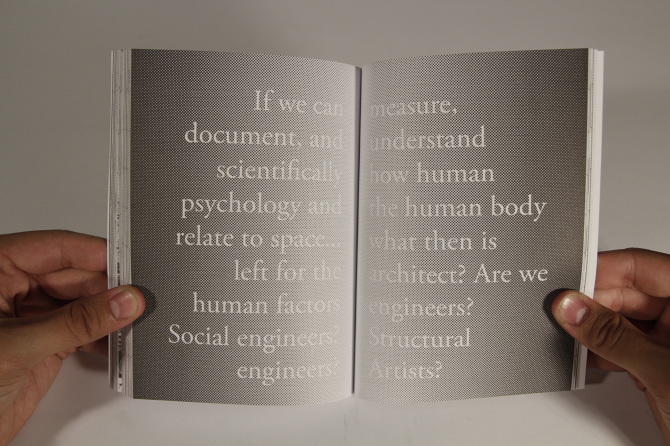

You see, this started as a simple attempt to capture a moment [1] in architecture. We were students [2] at the time, astounded by the pace with which conversations on architecture unfolded, and confounded by how quickly the topics of conversation changed. Camps sprang up briefly, held for a moment and then evaporated: parametricism, functionalism, environmentalism—whatever. It was all talk. Discourse was, in our estimation, an overabundance of opinion unfortunately deprived of reason. What was left when the lecture ended and the lights came on?

We tried to imagine an antidote to the situation. [3] We figured that by recording a series of conversations we might be able to pin down this slippery field and begin to measure its contours. We would question and parse the discipline, using the words of interlocutors to produce a cross-section, only to then push beyond. We could catalogue architecture’s alliances, produce an index of practices, and maybe even draw a map of its ideologies. And it was only going to take us a year.

Thirty-some-odd months later we can happily report that our work is not yet finished. Perhaps it’s barely begun. The pace of conversation has only quickened, and the necessity of stocktaking remains an urgent priority even if it will only ever remain incomplete. Time itself seems to move faster now. Moments pass. Quickly. Zaha is gone. Two biennales came and went. Now more than ever, “discourse” is confused and confusing. Yet we still feel the interview is our best hope for making sense of it all. Informal, quick, and dirty, the interview generates its own rules through dialogue. A record of “being in the moment,” the interview is not a belabored product of cogitation. It’s spontaneous and more or less authentic.

We present the transcripts, here, in print, to preserve the fleeting thoughts that might otherwise disappear into the void. Let the record show that these conversations represent positions in an expanding field of practice—travelogues of our personal search for what’s relevant today. At the very least, they’re an attempt to hold a mirror up to architecture: to which we humbly ask, “what do we talk about when we talk about architecture?”

[1] Long since past.

[2] Two of us still are students, for what it’s worth.

[3] And this is what you got.

By editors Chris, Phillip, and Mark.

Graphic design by Kyle J. Wing and Leah Wulfman.

Excerpt of Inteview with Wiel Arets

MTS: You’ve stated that being a stranger is a preferable condition in that it allows for freshness and thinking without preconception. Is it possible to maintain the guise of the stranger in a world which is, as you say, getting smaller? How do we step away and maintain that useful distance?

WA: What I mean by “being a stranger” is allowing yourself the opportunity to press a “reset button” every so often, so to speak. That means starting from scratch every day—the momentum of restarting helps a lot to provide a new perspective. As a student I read Paul Valéry, and every morning he woke up at 5:00 and started writing. He tried to forget and just write the first thing that came to his mind for maybe half an hour. In that sense, being a stranger doesn’t mean you have to go to Tokyo when you live in Pittsburgh—although that’s a big step. When you are a stranger, it means that you confront yourself with new environments. It’s the same thing as reading a book or hearing a story for the first time—it’s new to you. The first time you use a smartphone, you know it’s a phone, but suddenly you realize that it can do more things. You can use it as a platform; you can communicate easily with people you have never met in person. There is a sense of not knowing that accompanies entering a new society which in my opinion is a very interesting position to be in. The counterpoint to this “not knowing” is to rehearse every single day, like a soccer player, or Jiro Ono, the 89-year-old master sushi chef from Tokyo.

MTS: The documentary about him was insane!

WA: And after 89 years he still says, “I’m not perfect, I have to repeat, and repeat.”

MTS: When you were working and traveling in Japan, you interviewed some of the foremost architects working at the time. Are there any questions you used to kick yourself for not asking? More generally, during your education and when you were starting out, who did you learn the most from and what did they teach you?

WA: I can tell you what I believe. When I was a student—in my first, second, and third years—I wanted to be a soccer player. When you want to be a soccer player, you need competition, you need ambition—you need to be the best. It’s very important for a soccer player to look at and to analyze the best players. When I started studying architecture, I understood that you have to do the same, and so I started looking around me. I looked at the book that an architect from my town wrote and learned a lot about him, because I thought, if he’s so close, why do I need to travel the world to study others? He passed away before I thought to go to his studio, but I learned quite a lot from his library, an archive that I spent a year revamping, because he wrote and sketched in all the books he owned.

After that, yes, I went to Japan to write about [Kazuo] Shinohara, [Fumihiko] Maki and [Tadao] Ando, but before I went, I diligently studied their ways of working and thinking and as a result, when I wrote to them, I received responses very quickly. At that time, they were very responsive and all of them had time to see me as a young student. I remember them saying that you can learn the most from talking about the simplest of things. I remember sitting with Shinohara in a restaurant after we had been at his studio, and he talked about the House in White and the House with the Earthen Floor, from the 1960s. I then started asking questions about Tokyo and his writings about chaos and so on—on one hand, we spoke about the bigger picture, but on the other hand, we also would talk about the smallest details, like the floor he decided to make out of earth, or his House Under High Voltage Lines. Interestingly, when I looked at the work of these great architects and talked to them, I thought back to the Villa Malaparte, where I had once stayed for ten days with students from the AA. After those ten days, I understood that it was best to travel slowly—to go to a place and stay for some time. I later had the opportunity to stay in Villa Mairea for five or six days—a couple of days to live there, to actually be there. The same happened to me in Mexico: I went to Barragán’s work and met the people who worked with him. From all of that, I learned that it’s best to take your time—it’s better to look at one thing very carefully than trying to do too much at the same time. I never met Mies, but I think he’s a good example of someone who concentrated on certain things—better to read a book five times than reading five books once. I think that accounts for all important architects, writers or philosophers.

When I went the first time to see the work of Shinohara or Maki or Ando, and later Ito, I understood that they invested a lot of time in their work. You look at the work and you see the changes they made. When they designed a house they changed it many times—nowadays, some architects draw a sketch and believe other people should do the work of developing it and making it reality. I remember a young architect who worked in my office in Heerlen; at that time we had eighteen people working for me—four working day and night—and this architect, a previous student, asked me, “So I’ve been working here for three weeks, can I go downstairs to see everyone who’s making working drawings?” I said, “All of us here are making working drawings.” For me an architect has to make their coffee and their own drawings. It’s hard labor to be a good artist and a good architect. You have to push yourself. You can work with a team, but each of the team members has to take part in the thinking.

Architecture in my opinion is a discipline where we have to understand how we produce things and to do so, it’s important to go see these works in person. I had this moment where I was able to visit the Eames House when Ray [Eames] was still there, and it was so important to see that they lived their lives. Life means dealing with thinking and theory, but on the other hand life is also labor; the labor of putting things together. Those two concepts are the basis of everything we do. Messi as a soccer player can be very physically capable, but regardless he’ll always have intellectual moments of doubt while playing, asking himself, what do I do? That’s something you see with all good artists, too. Being impressed by what other people are doing is something I learned from those architects. In architecture, we can focus on so many different things, but if you take the opportunity to talk to people like the ones I mentioned to you, you will see they concentrate on one thing—just like Jiro Ono.